The Drifter is a good old-fashioned thriller

It’s a point-and-click adventure that tells a twisting mystery.

It’s a point-and-click adventure that tells a twisting mystery.

Point-and-click adventure games often tell silly, lighthearted stories. For me, the mishaps of the pirate Guybrush Threepwood in the Monkey Island series come to mind. The nature of the genre — wandering around, talking to people, and trying to solve puzzles — lends itself well to humor, as every interaction with a person or object offers an opportunity for a joke. The Drifter, a new point-and-click game from Powerhoof, cleverly uses the format to instead tell a dark, twist-filled thriller, and it sucked me in like a gripping novel.

In The Drifter, you play as Mick Carter, who you meet shortly after he hops aboard a train as a stowaway. Within moments you’ll witness a brutal, unexplained murder and be forced to go on the run, and the story quickly becomes a complex web of characters, pursuers, and mysteries to poke at.

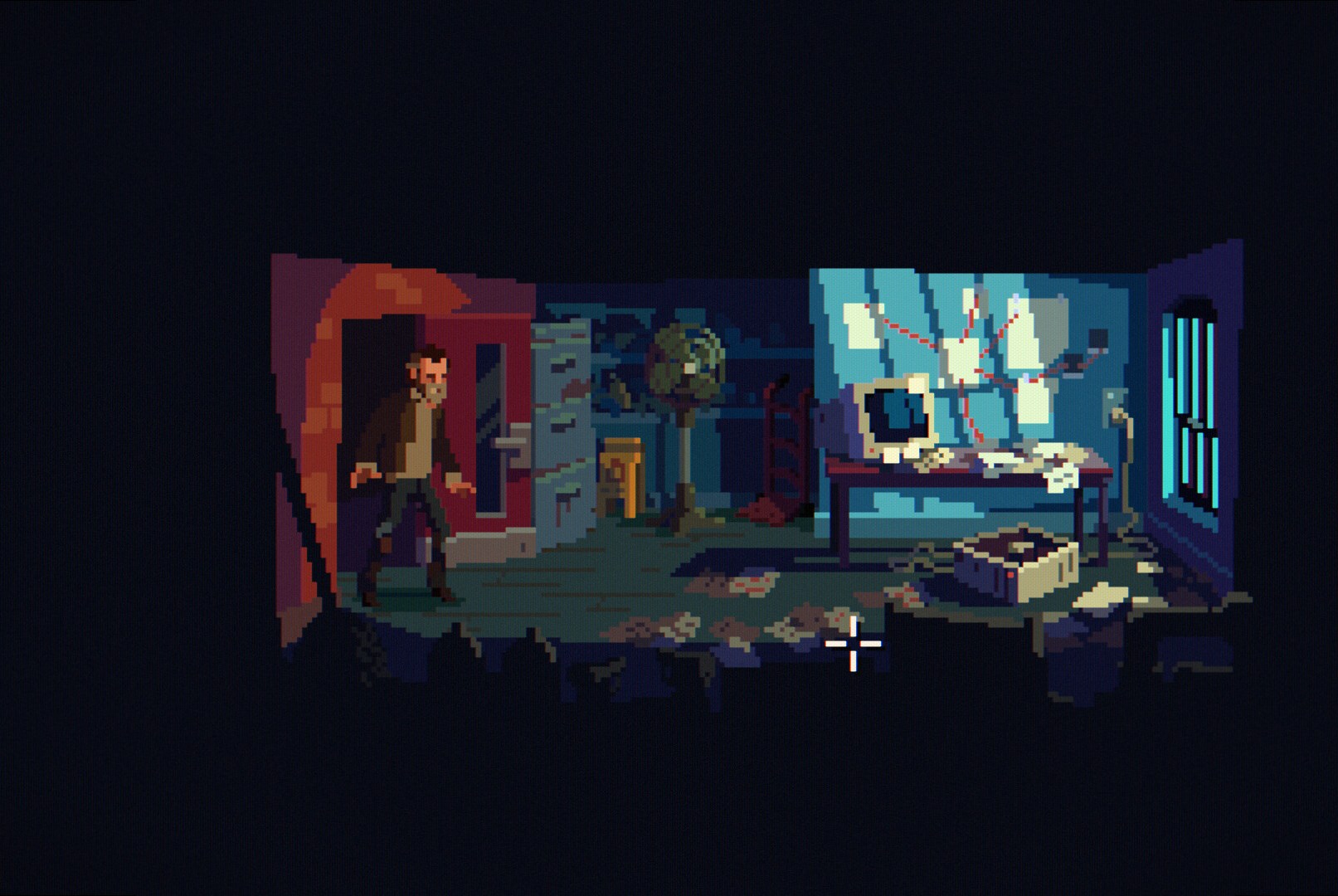

Mick serves as the game’s narrator, often describing what he’s doing in a grim, first-person tone with full voice acting by Adrian Vaughan. Mick’s tone sometimes feels a bit heavy-handed and overdramatic, but I enjoyed Vaughan’s performance anyway — it really sets a pulpy tone that’s fun to sink into. The game’s gorgeous pixel art helps, too, and locations have dramatic lighting and moody shadows.

This being a point-and-click adventure, the primary way to move the story forward is by solving puzzles, often by using the right object at the right place at the right time. The game is usually pretty good at suggesting where you need to go through conversations or through a list of broader story threads you’re investigating.

Actually doing the investigating is straightforward. I played The Drifter on Steam Deck, and it has a smart control scheme seemingly inspired by twin-stick shooters that shaves off a lot of the clunkiness of old-school LucasArts adventure games. You move Mick around with the left control stick, but when you move the right control stick, a little circle pops up around him with squares that indicate things nearby that you can interact with. You can select things you want to look at with a press of a trigger button. (You can, of course, use a more traditional mouse to play the game, too.)

More than once, though, I got completely stuck, and I often just brute-forced every item in my inventory with every person I could talk to until I found a way to move forward. I also occasionally leaned on online guides to figure out where to go next or if I missed something while investigating. When I hit walls, I really wished there was some kind of direct in-game hint system to give me a push in the right direction — this is an old-school issue with the genre, but a lot of modern games have figured it out.

Pushing through those more obtuse head-scratchers was worth it, though: in the later parts of my eight-hour run of The Drifter, the narrative threads all started to come together in some truly mind-bending ways. More than once, I stayed up way past my bedtime as I raced to figure out what would happen next.

I’m glad this story for Mick is over, but part of me hopes he runs into trouble again so I can cozy up with another point-and-click thriller.

The Drifter is available now on PC.